Pavlova in Paris

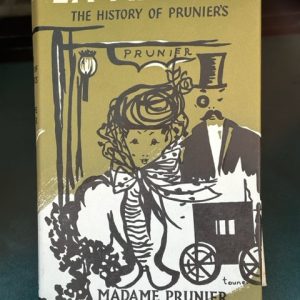

I recently lunched at the legendary Prunier restaurant in Paris’s Rue Victor Hugo. I had walked in front of this stunning art deco building many times, but never dared enter.

Prunier is an upmarket, classy restaurant specialising in caviar and other seafood products. This restaurant has a long and distinguished history, having opened in 1924, and attracted writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway as guests.

But the history goes much further back. In 1872 the original Mr Alfred Prunier and his wife opened a Parisian restaurant on Rue Duphot that bore his name.

The restaurant has just reopened under new owners, the Swiss investment group Olma Luxury Holdings, with a new menu by Michelin three-star chef Yannick Alleno.

From my very entrance, I was accosted by servers. Ultimately, a nice Russian lady, whose mastery of the French language was worse than mine, became my main server.

I decided to go straight to the heart of the matter, by ordering pasta with a caviar and cream sauce. It was pleasant, without being special. I swished down a class of Chassagne-Montrachet with my pasta – again, good, but not great.

Having already shelled out too many euros, I thought that I should go for broke. So I called for the dessert menu.

Lo and behold, I notice the famous Australian dessert, Pavlova, on the menu (New Zealanders erroneously claim Pavolva as their own). Pavlova is a unique dish based on meringue, with dollops of whipped cream and fresh fruit.

As I ordered my Pavlova, I decided to test the competence of my Russian server. In response to my question, she insisted that Pavlova was of Russian origin. Конечно Ivan, I think I heard her say.

So I whipped out my Australian iPhone and showed her the true (and Australian) origin of Pavlova. My dear Natasha was decidedly rattled!

I begged of her to stay calm. I helped her save face by insisting that Pavlova was named after the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova.

I explained to her that the proof is always in the pudding. I did not reveal however that I am a master taster of Pavlova!

From the first bite I knew that Prunier’s Pavlova was not the “Real McCoy”. The French seem to think that if you take a meringue and throw some cream and fruit on it, that you have a Pavlova.

“No Way Jose”!

Real Pavlova has a crisp and crunchy outer shell, and a soft, moist marshmallow-like centre, in contrast to meringue which is usually solid throughout. Prunier’s “Pavlova” was almost brick solid meringue!

This is not the first time that I have been disappointed by slap dash Pavlova preparation in France.

Indeed, it is highly curious. I have noticed an increasing number of French restaurants now serving Pavlova. But somehow none of them seem to get it right.